Good afternoon,

Is India’s protectionist streak making it harder or easier for it to become an AI powerhouse? We’ll answer that question and then close with Gupshup, a round-up of the most important headlines.

Have a question you want us to answer? Fill out this form and you could be featured in our newsletter.

—Shreyas, [email protected]

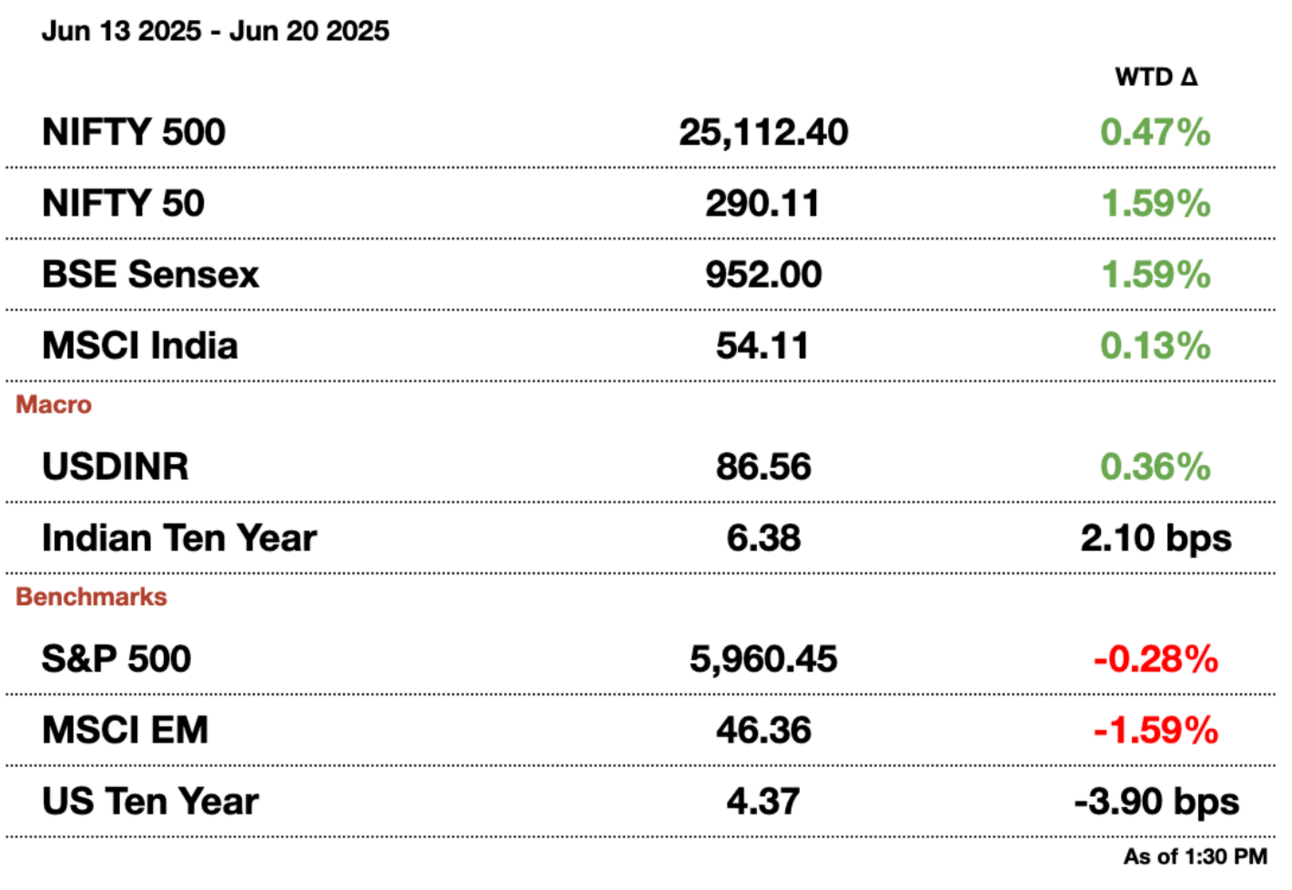

Market Update.

Is Protectionism Hurting or Helping India’s AI Industry?

India’s digital economy is booming, with over 850 million internet users and data consumption per capita among the highest in the world. But even as the country races to become a global tech and AI hub, it’s tightening the reins on how that data flows, especially when foreign firms are involved. At the center of this shift is a sweeping set of data localization requirements that mandate most companies store Indian user data on Indian soil. While policymakers defend the move as a matter of “digital sovereignty,” it’s presenting mounting logistical and regulatory challenges for global players looking to invest in India’s AI ecosystem.

The AI boom: Over the past five years, India has aggressively expanded its data center capacity. More than $40 billion (₹3.4 trillion) of investment is expected to pour into the sector by 2030, with hyperscalers such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud all announcing multi-billion-dollar investments in cities like Hyderabad, Mumbai, and Chennai. More than just server farms, these projects will be the infrastructure layer for India’s AI ambitions.

Training large language models or deploying generative AI tools requires massive volumes of structured and unstructured data. Local storage laws, such as those outlined in the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) of 2023, stipulate that personal data collected in India cannot be transferred outside the country without explicit permission from the government. This means that if a U.S.-based company wants to deploy a customer-facing AI chatbot in India, its training data, purchase history, conversations, and preferences must be housed within Indian borders.

That shift has triggered a scramble among multinationals to build or rent compliant infrastructure. Microsoft announced in early 2024 that it would construct three new data centers in India to comply with local rules, while Oracle partnered with Indian firms to set up cloud zones inside the country. Despite this activity, the buildout isn’t keeping pace with demand. Experts say available rack space in compliant facilities is lagging current needs by 20–25 percent, especially in high-demand regions like Bengaluru and Mumbai.

Infrastructure, regulations, and protectionism: The friction doesn’t stop at data infrastructure. India’s digital laws are governed by a complex matrix of regulations, including the DPDPA, the Information Technology Act, sector-specific guidelines from the RBI and SEBI, and newer proposals like the Digital India Act, currently in draft form. Together, they form one of the strictest data protection regimes outside of China or the EU.

Unlike the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, however, India’s laws are not just about privacy. They are also deeply protectionist. The government has explicitly stated its goal is to reduce foreign dominance in Indian cyberspace, particularly by firms that monetize Indian data abroad. One clause in the DPDPA allows the government to blacklist entire countries from receiving Indian user data, a provision that injects political discretion into corporate compliance. The net result is that foreign firms face not only logistical hurdles but strategic uncertainty.

Several multinationals like Mastercard and Visa were previously forced to spend millions building localized infrastructure after the Reserve Bank of India mandated that all payment data be stored domestically. This regulation delayed new product rollouts and onboarding processes, costing the company money. Meanwhile, companies like PayPal and Coinbase have either curtailed India-facing features or paused expansion altogether, reflecting the growing operational complexity foreign firms face under India's increasingly protectionist digital framework.

Part of the challenge lies in India’s broader business environment. While the government has championed tech investment through initiatives like Digital India and Startup India, bureaucratic inertia, slow environmental approvals, and infrastructure bottlenecks remain ever-present. Building a new data center still requires navigating state-level clearances that can drag on for 6–12 months. Power supply remains uneven, with diesel backup often the norm in Tier-2 cities. And compliance costs can be steep: firms often must hire local legal counsel, third-party auditors, and data protection officers just to maintain operations.

India is doubling down: Despite industry pushback, India shows no signs of retreating. In fact, the government has framed its data localization push as part of a broader national security and economic development strategy. Officials argue that data is the “new oil,” and letting foreign companies store it overseas is tantamount to outsourcing a critical national asset. During the 2023 G20 Summit, India explicitly called for global digital frameworks that recognize each nation’s right to control its own data flows, essentially a call to fragment the internet into more sovereign, walled-off ecosystems.

Policymakers also see local data storage as a prerequisite for building domestic AI champions. If Indian startups can’t access large datasets on home soil, they’ll never be able to match the scale or sophistication of Western tech giants. By forcing foreign firms to keep data in India, the thinking goes, the government is leveling the playing field. Already, firms like Reliance Jio, Tata Digital, and Infosys are investing in domestic AI models trained entirely on Indian-language content, models that might not have emerged without a regulatory moat.

Furthermore, there’s a political dimension. With national elections always looming, data privacy has become a populist issue. Framing foreign tech firms as exploitative or unaccountable plays well with both rural and urban voters. The government’s ability to regulate how these firms use data feeds into broader narratives of digital nationalism and economic independence.

The road ahead: Looking forward, India’s data policy is likely to become even stricter before it gets looser. A forthcoming amendment to the DPDPA may require firms to store certain types of "sensitive personal data" exclusively in India, even if permission exists to transfer other data abroad. Other proposals under consideration would give the government emergency powers to block data transfers in real-time.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Some foreign firms are exploring hybrid solutions, where anonymized or aggregated data is processed offshore while identifiable data stays local. Others are partnering with Indian companies to create joint ventures that sidestep some of the most difficult provisions. Indian regulators, for their part, are under pressure to clarify gray areas, especially around AI model training, inferred data, and cross-border analytics.

Ultimately, India’s data localization drive is about more than compliance. It’s a structural bet on the future of digital power, one that seeks to align the infrastructure of information with national interests.

If India succeeds in converting regulatory friction into domestic capacity, it could emerge not just as a market but as a serious producer of next-gen technologies. If not, its digital ecosystem may grow more insular, deterring exactly the kind of innovation it hopes to attract. Either way, the stakes have never been higher.

Want to reach out audience?

Email [email protected] to sponsor the next newsletter.

Gupshup.

Macro

India's infrastructure output rose 0.7 percent year-on-year in May, signaling tepid growth in core industries that form the backbone of industrial production. Weakness persisted in energy segments, with crude oil and natural gas output both declining compared to last year.

The Indian rupee ended slightly higher on Friday but fell nearly 0.6 percent over the week due to ongoing Middle East conflict pressures. Market relief came late in the week after U.S. President Donald Trump delayed a decision on military involvement in the Israel-Iran conflict.

Equities

Tesla will debut in India next month with showrooms in Mumbai and New Delhi, selling Model Y EVs imported from China. The launch marks the EV giant’s long-awaited entry into the value-conscious market, where high import duties and a $56,000 (₹4.9 million) price tag may challenge broader adoption.

DLF will launch a premium residential project in Mumbai next month, marking its return to the city after 13 years. The project, called West Park, aims to replicate DLF’s success in Delhi despite Mumbai’s oversupplied luxury housing market and the company’s past failed foray in 2005.

It’s raining deals in India’s equity capital markets with a flurry of block trades, IPOs, and share sales. However, investor sentiment remains cautious as many recent listings are trading below issue price and debut gains have been underwhelming.

State-run Hindustan Aeronautics has won a $59 million (₹5.11 billion) bid to commercially manufacture India’s small satellite launch vehicles, marking a major step in opening the country’s space sector to private players. The win positions HAL, traditionally known for fighter jets, at the forefront of India’s expanding space ambitions.

Eli Lilly said the response to its obesity and diabetes drug Mounjaro has been "positive" in India, where it is focusing on meeting growing demand. The U.S.-based company beat rival Novo Nordisk to launch the drug in India amid rising health challenges in the country’s large population.

Indian equity benchmarks rose on Friday, driven by gains in financials after the central bank eased project financing rules, and closed the week higher despite ongoing tensions in the Middle East. The Nifty 50 and BSE Sensex both ended the day up 1.29 percent, snapping a three-session losing streak and posting weekly gains of about 1.6 percent.

Software services firm Cognizant Technology Solutions will invest $183 million (₹15.9 billion) to build a new campus in Vishakapatanam, India, creating around 8,000 jobs. Commercial operations at the campus are expected to begin by March 2029, according to the Andhra Pradesh government.

Indian courier delivery firm Delhivery launched its short-haul parcel transport service in two cities, increasing competition in a market led by Uber and Porter. The service currently operates in the national capital region and Bengaluru, with plans to expand to other major metro cities as Delhivery seeks to diversify amid competition in long-haul freight.

Indian state fuel retailer Hindustan Petroleum Corp plans to invest about $231 million (₹20 billion) to build 24 compressed biogas plants over the next two to three years. This move supports India’s carbon reduction goals by increasing cleaner fuel production from organic waste as part of its 2070 net-zero target.

India's HDB Financial IPO pricing is based on the company's fundamentals and not influenced by the roughly 70 percent premium seen in the informal 'grey market,' bankers said. The shares are set to be sold at 700 to 740 rupees each, while the grey market trades them around 1,200 to 1,250 rupees.

Alts

Driven by affordability and internet access, 23 percent of Indians relied solely on mobile phones for media consumption in Q1 2025. The trend, led by rural and lower-income users, is prompting companies like Netflix and Amazon to tailor mobile-first strategies for India’s vast digital market.

Global trading giants, including Citadel Securities and Optiver, are rapidly expanding in India’s booming derivatives market, triggering a surge in talent demand and exchange infrastructure upgrades. Their hiring push follows soaring local trading volumes and rising optimism that India’s investor base can weather global volatility.

Policy

India's central bank on Friday reduced the mandated portion of lending that small finance banks must extend to priority sectors by 15 percentage points, lowering it from 75 percent to 60 percent. This move aims to give small finance banks more flexibility while still supporting key areas like agriculture and small businesses.

See you Monday.

Written by Eshaan Chanda & Yash Tibrewal. Edited by Shreyas Sinha.

Disclaimer: This is not financial advice or recommendation for any investment. The Content is for informational purposes only, you should not construe any such information or other material as legal, tax, investment, financial, or other advice.